Robert Steinhilber Stories

Mohammad

Hanif

and the

Box of

Doom

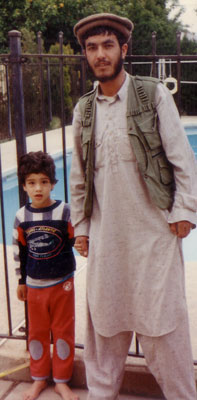

Hanif has no legs. You would never know it- he rides motorcycles like a pro. He stepped on a land mine when he was 19 years old and US Army doctors in Germany got him a pair of incredibly heavy WWII vintage wooden prosthetics. He wears them like they grew there. He can dance.

One time my wife Mica and I took Hanif camping. We left in the early evening. Past midnight,

we were passing through the old mining town of Globe, Arizona. Hanif sat in the passenger seat of my little brown Chevi, rocking out to my collection of Pashto music tapes when he inadvertently kicked over a gallon of water without knowing it (no legs- no feeling in them wooden legs!). When I realized there was water sloshing around, I pulled over into the parking lot of a real estate office to clean things up. It was pitch dark outside.

I had to take everything out of the car to dry it all, and it being dark, I accidentally left my briefcase on the ground when we drove away. Hanif called it my “bakseedastah” in Dari, a plastic AMWAY samples case containing all Hanif’s travel papers, as well as the microphones for my band.

The next morning I discovered the box was missing. We looked everywhere. I drove back from our campsite, all along the highway miles and miles, through Globe, Miami, Superior, and back. It was nowhere in that parking lot where we had stopped. Finally we went to the Globe Police Department, and asked if anyone had found a black plastic AMWAY sample case along the highway. They said they couldn’t help us, but suggested we visit the Highway Patrol station. Actually, they sort-of insisted. They directed us there and made sure we found it.

The Highway Patrol were courteous and helpful. They separated the three of us into small rooms and subjected us each to several long sessions of questioning by different officers. They never said anything about having found my bakseedastah.

Finally an officer took me alone out to a patrol car and we drove several miles out of town. Still no explanation for any of this. He pulled over near a large empty piece of desert, maybe an acre of land, completely surrounded by a 10-foot fence topped with a Y-shaped formation of razor wire.

“Is that yours?” He asked, pointing to the center of the field.

“What?” -I didn’t see anything.

Then I saw it. It was so far away, and so dwarfed by the size of the empty field that I had missed it.

“My Briefcase!”, I exclaimed.

“Go pick it up”, the officer commanded.

I did as he said. I walked to the middle of the field. I opened the briefcase. I could see the officer flinch. Inside not a thing was missing. They had not opened it- because they had never physically touched the box. It had been carried to that location on the end of a 16-foot pole attached to a flatbed truck, by the Arizona HP bomb squad… They were that afraid of it. I patiently but nervously began to explain to the officer the meaning of all the Arabic-looking Pashto and Dari documents in my briefcase. He didn’t care, and he hadn’t seen any of it anyway.

Breathing obvious relief, the officer told me that when an employee had arrived at the real estate office that morning, she had called the Police to report the presence of the mysterious black plastic object, and communicated her fears that it might contain a bomb planted by an angry, homeless former mine employee. What we did not know was that the real estate office where we stopped the night before had recently received some bomb threats, owing to the fact that they were selling houses that had been foreclosed on mine workers who had lost their jobs and everything elsewhen Phelps-Dodge closed the copper mines. The Police and Highway Patrol acted as they are trained to do when they believe there is an explosive device present. They were planning on blowing up my briefcase as soon as they had completed the necessary preparations to do so. I was just in time!

This was over a decade before “nine-eleven” and the “war-on terrorism”. The HP officers and staff entertained us with fine-style hospitality before sending us on our leisurely way with coffee cake and other goodies.

Hanif, beaming, shook hands with every one before we left. Shaking hands is a big deal with Afghan people.

“You are my Brothers!” he repeated to each, regardless of gender (not knowing much English), and “See you later Alligator”, something else I taught him.

Hanif stayed with us for several months, and when he had to go home to Kabul, he gave me a phone number in Washington DC where he said I could reach him- the home of a man named Mr. Karzai.